James Galvin tries to penetrate the fog surrounding how the Royal Navy ends up with warships that have potentially fatal flaws, suggesting similarities with events a century ago. He also looks at the disconnection between what politicians think warships are for and their actual purpose.

“There is something wrong with our bloody ships today!” So said Admiral David Beatty at the Battle of Jutland 100 years ago after witnessing the loss of the battlecruisers HMS Queen Mary and HMS Indefatigable. They had been destroyed by German shells, with great loss of life. What is less well-known is that he went on to say to his Flag Captain, Ernle Chatfield (like Beatty a future First Sea Lord): “and our systems too.”

The Ministry of Defence (MoD) has recently admitted that the Royal Navy’s six Daring Class (Type 45) destroyers have significant engine problems that could at critical moments seriously inhibit their ability to perform the tasks for which they were designed. As the Royal Navy has only 19 frigates and destroyers this is a serious problem, potentially robbing an already overstretched fleet of badly needed vessels.

On Saturday, January 30, five out of six Type 45s were alongside the wall at Portsmouth Naval Base, with the MoD attempting to put a positive spin on the situation. One of them, HMS Dauntless, has allegedly been reduced to the role of a harbour training ship until new main engines and diesel generators are available to be fitted. The others would, hopefully, be able to resume active duty until their power supply problems are fixed (a process the MoD says will begin in 2019).

At least with the casualties in Beatty’s Battle Cruiser Fleet (BCF), the fault could be pinned to the procurement definition for the ships. Despite all his many talents and great service to his beloved Royal Navy and the nation, Admiral Lord Fisher was the major instigator behind the concept (and therefore the tragedy) of the well-armed, but lightly armoured (compared to battleships) battlecruisers lost at Jutland.

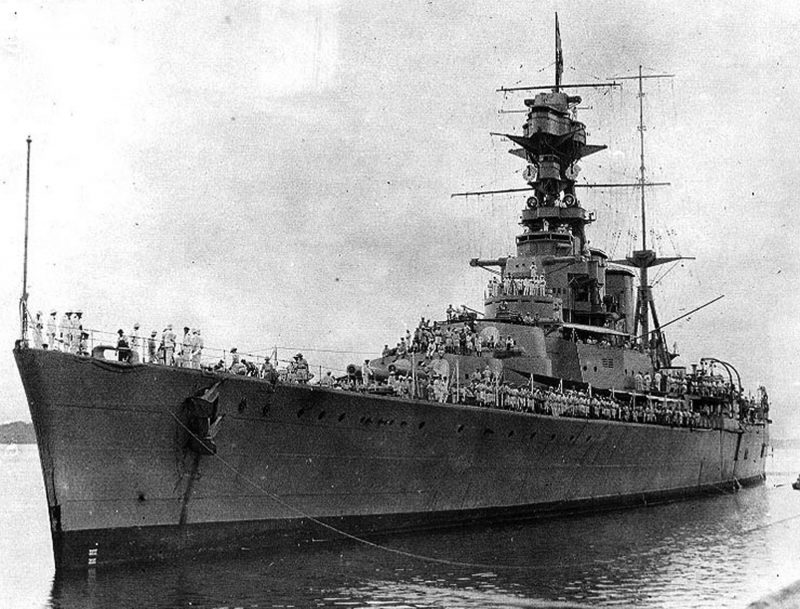

There would be a sequel in WW2, when the HMS Hood (completed in 1920) was also blown apart when facing the Nazi battleship Bismarck in the Denmark Strait. It was final proof of the fatal flaw of building capital ship-sized cruisers (and then failing to reconstruct them with better protection or replace them with proper battleships).

The battlecruisers were not designed to take heavy punishment from 11-inch and 12-inch shells, and certainly not 15-inch projectiles. Nor were they designed to engage battleships. The sole occasion when British battlecruisers were used in the way that Fisher had envisaged, they wiped out a German cruiser squadron at the Battle of the Falkland Islands (in December 1914). In that engagement Fisher’s so-called “greyhounds of the seas” did the job for which they were designed – overhauling and overwhelming less powerful enemy commerce raiders.

Referencing Lord Fisher is appropriate, as his name recently cropped up in the evidence given by Admiral Lord West, a former First Sea Lord and Commander-in-Chief Fleet, Defence Select Committee of the House of Commons. The context was, however, not Type 45 destroyers but the concept and design of the Royal Navy’s new aircraft carriers, HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Prince of Wales. To some they might seem to share with the Type 45s and Fisher’s battlecruisers the fatal disconnection between purpose and design (and, potentially, exposure of a lethal flaw on operations).

Traditionally British warships were conceived and designed within what was the Ministry of Defence (Navy). In Admiral Fisher’s day (and until 1963) it was called the Admiralty. Both titles are now redundant as the whole concept of military thinking, planning, design and procurement is joint service.

The 2010 and 2015 Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR) documents are littered with the word Joint. The MoD has been bathed in the colour purple and has, allegedly, a joined up concept of operations. The role envisaged for military equipment seems to be the product of joined up thinking, with input from all three armed forces to a greater or lesser extent.

While the RAF has become deeply embedded within the strike carrier programme it is hard to envisage the RN being allowed to insert itself into RAF fast jet programmes (such as Typhoon upgrades). Nor would the Navy have a say on a new tank for the Army except for making sure it can fit in a landing craft and an assault ship well-deck.

Judging by his evidence to the Parliamentary Defence Committee [HC 682 of January 14, 2015], Admiral Lord West was not altogether sure who came up with much of the project definition for the new carriers. In its desperate striving to show the Navy is relevant to the UK, has the RN gone too far in contracting out key decision-making that in the past it would have handled solo (and quite rightly)? Not only has the MoD become purple and ‘joined up’, it has not had a naval officer as Chief of the Defence Staff since Admiral Lord Boyce vacated the post in 2005.

Admiral Boyce did not suffer fools gladly, so perhaps politicians of all parties see naval officers as trouble? Politicians dislike being disagreed with about certain matters of strategy and military procurement, often regarding their uniformed advisors as speaking inconvenient truth to power.

It is notable that David Cameron hauled the incumbent First Sea Lord over the coals in 2011 for explaining that strike carriers would have been very useful in projecting power from the sea during NATO’s Libyan campaign. The UK government had just axed Britain’s Harrier carriers, yet the same sort of strike jets and ships were used in that war to great effect by Italy and the USA. The French contributed their full-scale nuclear-powered strike carrier Charles de Gaulle. A British carrier would have been a superb boost to operations in a campaign waged across territory conveniently adjacent to the sea.

The Royal Navy instead won its spurs with naval gunfire support against shore targets, mine clearance and also controlled air strikes by land-based aircraft while deploying Apache helicopter gunships and Airborne Surveillance and Control (ASaC) helicopters from HMS Ocean. Clearly there is a lot for the RN to do in modern campaigns (and the Charles de Gaulle has recently mounted air strikes against targets in Syria and Iraq, an example of something the UK should also be doing).

The new carriers must be able to generate at least the same level of sorties as the Charles de Gaulle, provided all the right decisions have been made to enable them to stay on deployment without some serious Type 45-style flaw intervening.

During the Defence Committee hearing, Admiral West was asked about decision-making in Defence, specifically in relation to the design and role of the Queen Elizabeth Class aircraft carriers. Lord West thought the design, role and so forth stemmed from the defence reviews of the late 1990s. These set out that there would be two larger carriers to replace three smaller Invincible Class carriers. Lord West thought that these ideas were drawn up by: “Policy people at the centre and the Permanent Secretary.” They were then inserted into the Defence Reviews.

The Chairman of the Defence Committee asked Admiral West if it was difficult to pin down who made such decisions within MoD. Admiral West replied it was “unbelievably difficult” to do so. He went on to add that it was not like Fisher’s day.

Nor was it like more recent times when a naval requirement would lead to a specific ship for a certain job – and if that job disappeared so would the ship.

Problems tend to creep in when a specific person, or political rationale, overcomes the logic in terms of likely naval warfare tasks and more general maritime operations, the battlecruisers being a case in point. Fisher thought the concept was fantastic (when it was deeply flawed). The general public were so enthusiastic for as many of the glamorous battlecruisers as possible that politicians bent to their will and built more of them. The Type 45s have been continually sold to the British people as the best in the world, capable of shooting down tennis balls (!?) but they aren’t much good if they have a massive power outage and shudder to a halt in the water.

The Type 45s were envisaged as the replacements for the Type 42 destroyers. The latter served the RN well and saw action in the Falklands, in the Adriatic during the 1990s and both Desert Storm and the Iraq War and other heated periods of peace. Either they were part of a (Invincible Class) carrier task group or performed in their designed air-defence role, but – solo or as part of a larger whole – they also became multi-tasking platforms and functioned pretty well.

The propulsion for the Type 42s was based on gas turbine, main and secondary engines. The Type 45 destroyers were designed around a propulsion system based on electric drive powered by gas turbines and diesel generators. The same propulsion combination is being fitted in the two new carriers, but obviously on a bigger scale. It is to be hoped that the carriers don’t suffer the same sort of problem as the Type 45s…but on a bigger scale.

The future of the UK’s maritime defence and the ability to project power depends on it. To lose power at a critical moment in the heat of battle – denied the ability to move and to operate combat systems and sensors – could be the equivalent of the battlecruisers’ fatal flaw (and fate) at the Battle of Jutland. Ships and lives could be snuffed out.

That the major work packages for each destroyer are not to start until 2019 is extraordinary – it shows a remarkable level of complacency in government that funds are not being made available immediately. These are, after all, billion pound ships that are meant to protect the new carriers, the first of which is to commission in 2017. It is hard to escape the notion that the UK government no longer sees warships as fighting in wars but just as employment vehicles or sovereign pieces of real estate. They are totems to show off but never to risk in a fight.

One government minister last year revealed that the UK does not envisage losing a ship in combat ever again. Lord Astor of Hever told the Defence Committee: “In determining fleet sizes no specific provision is made for the possible loss of ships on war fighting operations. The Royal Navy has lost just four frigates and destroyers to enemy action in the last 50 years, all of which were during the Falklands War, and steps have been taken to learn lessons from these losses. Ship design, capability, training and doctrine all play a part in maximising operational effectiveness and help to ensure ship survivability.”

At the time the Defence Committee observed rather acidly in its report: ‘This answer implies that the planning assumption is for zero per cent attrition. In other words, in the 19 strong frigate and destroyer fleet there is no spare capacity to meet unexpected demands or breakdowns or to cope with the loss of ships to hostile action. This partially reflects the fact that SDSR 2010 was conceived at a time when the expected enemies (insurgents or terrorists of an Afghan or Iraqi type) were not expected to have a navy, (and certainly not vessels capable of sinking Royal Naval ships).’

Indeed, for the primary reason the RN has only lost four frigates and destroyers in 50 years is that it has not faced a serious opponent, or at least not one with the terrifying capabilities today possessed by, say, China and Russia.

SDSR 2015 did not change that fatal attitude and in fact reduced the anticipated number of future Type 26 frigates from 13 to just eight, with vague promises of other surface combatants from David Cameron to try and placate Scottish shipyard workers.

The size of the Royal Navy of today seems not to be dictated by front line reality, where conventional naval threats are mushrooming alarmingly. If any major state versus state war erupts and involves the RN it will involves casualties, of that there can be no doubt. There have been very few wars in which Britain did not lose warships to enemy action. It would be wise to ensure those ships the British fleet does possess are not fatally flawed in themselves due to UK govt defence incoherence.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item