To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Jutland WARSHIPS IFR Editor Iain Ballantyne tells the story of how events unfolded from the perspective of the British battle-cruisers and super-dreadnoughts.

The Kaiser’s Navy described it as ‘Der Tag’ or The Day, which is what the British called it too. A long awaited reckoning. There had been so many damp squibs and hesitant clashes in the North Sea where the battle fleets nearly but not quite locked horns.

The British and German navies were like knife fighters in a darkened room, circling around each other, trying to gauge the best time to thrust – or to lure the enemy into making a lunge that exposed him to a deathblow.

Both sides had during nearly two years of war tried and failed to encourage the other’s main battle fleet to fight. The Germans aspired to isolating a portion of the Royal Navy’s main striking force and destroying it via local superiority.

This, so they hoped, could be completed before the great hammer of the Gods that was the full Grand Fleet of the Royal Navy could descend. Uppermost in the mind of the methodical, cautious Admiral Sir John Jellicoe – commander of the Grand Fleet – was the thought that he could, in the words of First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill, win or lose the war in a single afternoon.

Should Jellicoe deploy the Grand Fleet in a careless fashion and suffer a defeat then Britain could be knocked out of the war. It was a crushing responsibility. Yet it was the hard-charging Vice Admiral Sir David Beatty – leader of the Battle Cruiser Fleet (BCF), the semi-independent fast attack force – who had so far gained the laurels, becoming Britain’s first superstar fighting admiral since Nelson.

There were those who wondered if Beatty quite deserved the accolades he received for his less than decisive victories at Heligoland (August 28, 1914) and Dogger Bank (January 24, 1915).

Britons expected a triumph on the scale of Trafalgar and preferably as soon as possible but Beatty’s victories so far were not that kind of decisive blow against the enemy. They did, however, provide a startling insight into the kind of radical new combat now being waged at sea.

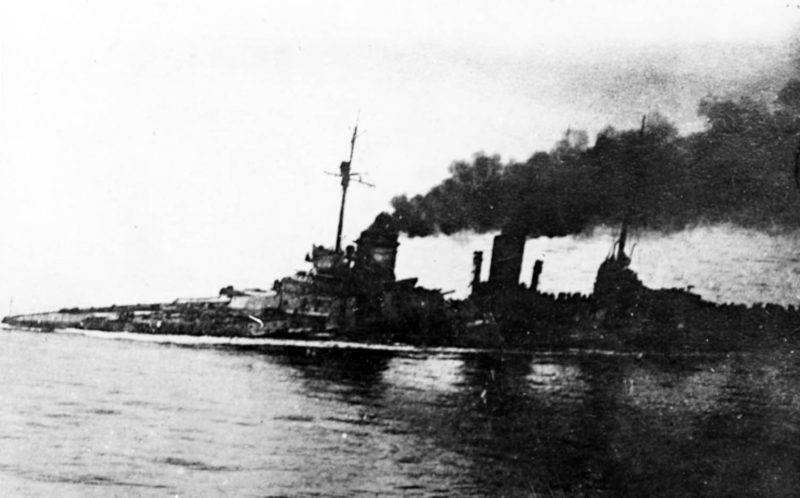

The speed of sea fighting in the age of super-dreadnoughts and battle-cruisers left no room for trial and error and opportunities to scale the steep learning curve were few and far between. The moment you realised that you had it wrong could be when your ship was blown apart. Twice the BCF had stormed into action but some of its ships suffered serious damage while the profligate expenditure of heavy ammunition led to a frustrating curb on rates of fire.

This was deeply aggravating for Beatty who had at least some experience of the breakneck speed of the new warfare. He had been required to make instant decisions as massive capital ships hurtled into action and there had never been anything like it. In Nelson’s day warships sailed into battle at a walking pace (two or three knots) and the engagements were often at a pistol shot’s distance.

More than 100 years after Trafalgar the pace had become almost faster than the human mind could deal with – a fleet commander and his key officers were tasked with making so many split-second calculations and adjustments to try and hit an enemy miles away. They had no computers with microprocessors, just their brains and their eyes, assisted by what was, for its day, advanced gunnery control equipment (but was actually rather primitive).

Huge vessels displacing at least ten times the tonnage of Nelson’s immortal HMS Victory leapt forward at 26 knots (or more) packing a punch that could swiftly have turned that old man-o-war into matchwood.

Beatty’s flag captain, Captain Ernle Chatfield, noted with wonder that things now unfolded in combat with seconds stretched out to an eternity. What Chatfield thought was half an hour’s fighting at Heligoland actually lasted five minutes. It was all about leaning forward, casting the mind – indeed the whole being – ahead in time to anticipate the next move – where the next salvo should fall to catch the enemy, and where his might make impact.

The gigantic guns – including the 13.5-inch weapons of Chatfield’s battle-cruiser Lion – were so loud that those exposed to the awesome sound and the sheer shock stopped hearing them. Beneath the skin of a capital ship hundreds of sailors worked like automatons – just cogs in the terrible, mighty machine – feeding massive shells to the ravenous guns. Conveyors and lifts took the cordite and shells up to the gun crews. Automated rammers pushed them all home, the breech was closed and the weapon elevated, the turret turning – sniffing out the prey.

A gunnery officer in his eyrie – a control centre in a box mounted at the top of a mast, high above the funnel smoke – made his calculations and pressed a button.

A bell dinged loudly in the turret – guns already laid on target – and BANG! Great gouts of flames, dirty yellow and black smoke, vomited from the muzzles, paint burned off their snouts. The shells zoomed away in a fleeting blur on their lethal parabola.

• To read Iain Ballantyne’s account of Jutland in full buy the June 2016 edition of WARSHIPS IFR.

For the story of HMS Warspite’s fighting life see Iain Ballantyne’s book ‘Warspite’

For a potted history of the battleship HMS Warspite watch this video: Click Here

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item