(From the March 2015 edition)

by Usman Ansari

Bedeviled by project management and technical issues though it was, the cancellation of the Nimrod MRA4 in 2010 left a hole in Britain’s maritime defences that now appears open for exploitation by Russian submarines. US Navy, Canadian and French patrol aircraft had to be seconded to Britain at the end of 2014 in order to carry out searches for suspected submarines off the Scottish coast.

During the Cold War and right until 2010, the Nimrod – dubbed the ‘mighty hunter’ – regularly scoured the seas around the British Isles and further afield for any sign of intruding submarines. Nimrods provided top cover for Royal Navy (RN) ballistic missile submarines as they departed on deterrent patrols.

More than 20 years on since the end of the Cold War, and half a decade on from the surprise decision to ditch the MRA4, Russian submarine activity certainly appears to be increasing. The loss of the MRA4, and the prior retirement of the Nimrod MR2, has rendered the UK unable to perform vital surveillance duties while also radically reducing Search and Rescue (SAR) capability.

The cancellation of the MRA4 left a bitter legacy. It has been claimed in various quarters that the RAF did not defend the programme vigorously enough as it preferred to safeguard its Tornado and Typhoon fast jets from potential cuts. The RN for its part has been forced to fill the gap in maritime surveillance and Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) capabilities with already hard-pressed frigates and Merlin helicopters.

It is likely that had the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) been operating the Nimrod, rather than the RAF, it would not have gone. The MRA4 certainly promised awesome patrol range and endurance, combined with the cutting edge sensors and a formidable armament, all of which would have been useful in the Libyan War of 2011 and ever since in combating terrorism and piracy.

Following Nimrod’s demise there was speculation the Navy would push to operate whatever the replacement turned out to be. Despite there being a strong case for any such future patrol aircraft to be an FAA asset, it will almost certainly be once again operated by the RAF. It is keen (post-Afghanistan) to expand its involvement in more than just fast jet operations.

There has been speculation since September 2014 that four US Navy P-8A Poseidon MPAs are to be leased in order to provide maritime surveillance and attack cover. Many analysts have considered Poseidon’s eventual purchase as a Nimrod replacement a foregone conclusion. Officially no decision will be made until the forthcoming Defence and Security Review (DSR) is completed.

Other Maritime Patrol Aircraft have been offered to the British. For example, in 2012 Saab proposed the maritime patrol variant of its Saab 2000 twin turboprop regional airliner, the Swordfish. However, such an aircraft does not approach the endurance, mission, payload, and range capabilities of Nimrod over blue water. It is difficult to see it as a viable option.

Japan’s offer of the Kawasaki P-1 does, though, present an interesting possibility.

If successful, it would be Japan’s first major defence export outside the Asia-Pacific region and worth over US $1 billion. Britain’s procurement would mark the P-1 as a genuine candidate for other nations that are also seeking a new patrol aircraft, such as Canada, Norway, and New Zealand.

They need to phase out their P-3 Orion (Norway and NZ) and Aurora (Canada) aircraft, which P-1 was specifically designed to replace. It is uncertain what a P-1 variant (or indeed a P-8) tailored to British requirements would cost, but the P-1 is slightly larger that its US competitor, and more generally comparable to the cancelled MRA4, albeit with a shorter range.

The P-1 is said to cost around $142 million while the P-8 is up to $134 million more expensive per aircraft. There may perhaps be an advantage in the P-1 having four engines, allowing two to be shut down to conserve fuel when on extended patrol as was the case with the Nimrod.

It is likely there could be a greater element of joint production if the Japanese option is selected, with more British content than there would be in the P-8. This may belatedly offset at least some of the damage done to British industry when the MRA4 was scrapped and therefore be a strong incentive to select the Japanese aircraft.

Japan’s export drive with the P-1 comes at a time when its defence budget has undergone an increase for the third consecutive year, edging up 0.8 per cent, to US $41.12 billion after over a decade of cuts. This is essentially to counter China’s rapid military modernisation but also with an eye on disputes China has with its other Asian neighbours, as well as the nuclear threat from North Korea.

The need to defend island possessions and conduct maritime surveillance over vast areas will see Japan purchase twenty P-1 aircraft to begin replacing its large fleet of P-3C Orions. For Britain the stimulus has been the sudden awareness that it has created a gigantic hole in its maritime security in home waters that any serious player on the global scene would not hesitate to fill. Begging and borrowing MPAs from friends will not do.

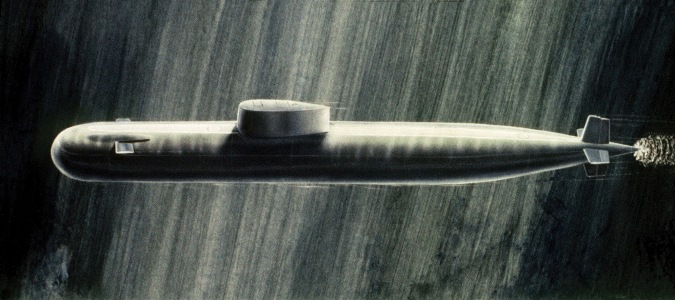

Pictured Top: An artist’s impression of a Russian Navy submarine on the prowl below the waves.

Image: US DoD.

Japan’s contender to fill the current British MPA capability gap, the Kawasaki P-1.

Photo: JMSDF.

Comments

Sorry, comments are closed for this item